By the end of the 1980s, my dad’s Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme was starting to show signs of aging. As a kid, I knew nothing of the mechanical problems plaguing The Great Silver Beast, but something must have been wrong if we were borrowing my grandmother’s car for a road trip. That was fine with me at the time, because it meant sweet relief from the black vinyl seats and metal seatbelt buckles of the Cutlass—both of which reached the temperature of a microwaved Hot Pocket when they sat out under the Texas sun.

I don’t remember much about Grandma’s car. My vague memories hold the image of a red sedan not unlike the Cutlass, some ’70s-era holdover from the age of big, blocky automobiles. The interior was also red—some kind of ultra-soft cloth that didn’t burn your legs when you sat on it in shorts. The ashtrays in the door handles were metal, opened and closed with satisfying clicks, and held remnants of recently smoked cigarettes.

What I do remember, as much as anyone can while looking forty years into the past, was the fact that Grandma’s car talked. Nobody prepared me for this, and I like to think Grandma encouraged me to open the door and sit inside, well aware of the surprise that awaited me.

The door is a jar.

Aside from Knight Rider’s KITT, I’d never encountered a vehicle that could talk, and yet here was this strangely robotic voice informing me that the door was “a jar.” Even at that age, I knew the difference between doors and jars, and so I’m now able to pinpoint the moment in my life where I learned a new word: ajar.

The door is ajar.

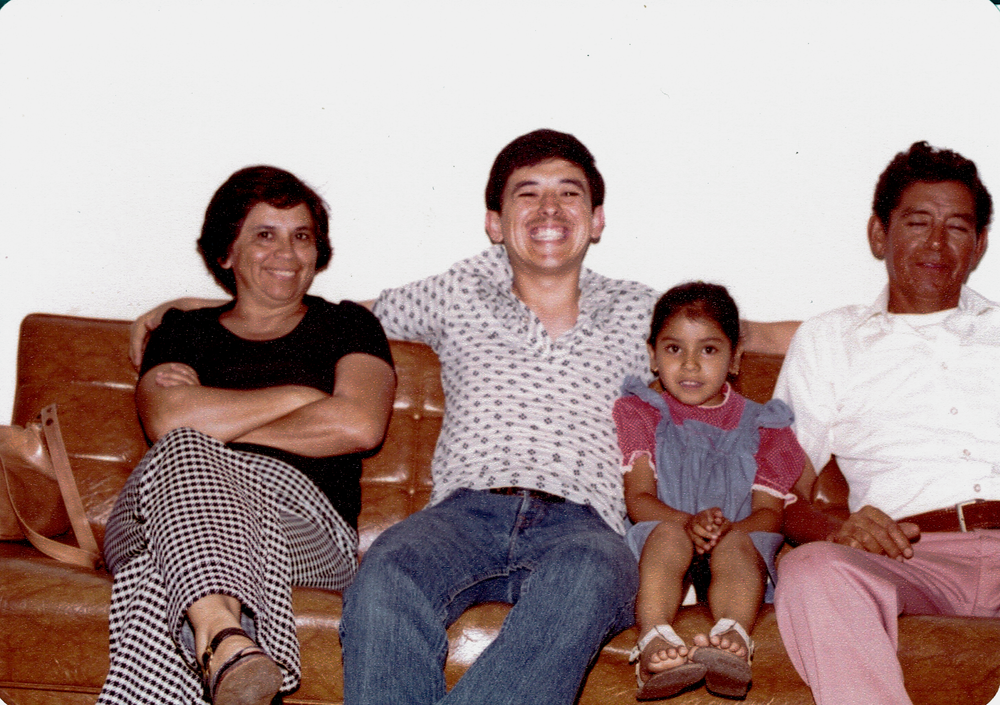

Grandma was born Cruz Trevino in Pearsall, Texas, in 1932. And yet, I don’t have any memories of her until after 1988, when my family returned from a tour in Italy. I know I met her before we left the States, but those interactions are lost to me. Coming home was like meeting her for the first time, and it’s from those years that my memories of her built like a fresco across a wall. She was loud, brash, endlessly warm, and loved my brothers and me like we were her own children. She spoiled us rotten, not as a way to win favor or torture my parents, but because that was her way: to give, to serve, and to care for.

It was strange to meet someone who already knew me—who knew my parents more than I could understand at the time. There was familiarity there, but it was one-sided. Throughout the late ’80s and early ’90s, we would visit her in her home on Staples Street in Corpus Christi, Texas. During one visit, I fell asleep early, and someone took me to an unfamiliar bed. When I woke up in the middle of the night, with the curtains blowing over the open window, and a shadowy figure lying next to me, I was understandably upset. But then a voice spoke.

“It’s alright, it’s me.”

And like a tactless child, I asked, “Me who?”

When her laughter filled the room, I knew I was safe. The moment amused her so much that she retold the story over breakfast, and it took a few years for me to live it down. But that was her style—nothing fazed her. My parents have plenty of stories of Grandma being mad or angry or not so nice, but I never saw that part of her. Not once. She was always so loving, and even when I was being ungrateful or aloof, she never wavered.

The keys are in the ignition.

I remember sitting in the passenger seat and playing with the ashtray while Grandma explained the car’s inner workings to my dad. She often spoke in a mixture of English and Spanish, which meant I only understood half of what she was saying. That’s where I learned the word maquina, which I thought she was using to refer to the car, but could have been a reference to the engine. I would sit in that passenger seat only one other time, when Grandma asked me if I wanted to go with her to get some corn.

Looking back, I might have keyed in on the fact that she didn’t say to the store, rather that we were just going somewhere to get corn. That somewhere turned out to be a random farm on the outskirts of Pearsall. When Grandma started pulling off to the side of the road, I thought maybe something was going wrong with the car. Except, there had been no voice telling us the engine is overheating or your tires fell off. Once stopped, Grandma got out, opened the trunk, then pointed to a nearby wire fence.

“Go get some corn,” she probably said. “Just climb in there.”

It wouldn’t be the first time Grandma and I committed a crime together.

After returning from Italy, we were stationed at Goodfellow Air Force Base in San Angelo, Texas, which meant we only saw Grandma on holidays and in the summer when we’d all head out to Padre Island for fried chicken and painful sunburns. Her home on Staples Street always intrigued me because it was set back from the main road with what amounts to an alley between them. We’d pull off the road into this little asphalt strip, and before we could get parked, Grandma Cruz would be running out of her front door to greet us.

Unless she was working, which she often was.

For more than thirty years, she worked as a store manager at Maverick Markets, the Corpus Christi version of a 7-11 or Circle K. If we arrived in town during her shift, we’d usually stop by her store to say hello. As soon as we entered, she’d come running from behind the counter to scoop me or one of my brothers up. Her voice would fill the store, drowning out whatever Tejano or rock radio was playing in the background. Once she had hugged and kissed us all, we would continue on to her house where one of my uncles and some of my cousins would often be waiting. And when she got off work later and returned home, she was never too tired to sit with us, make us dinner, and spend the entire night visiting.

Even though we’d visit late into the night, Grandma usually had to be back at the Maverick early the next morning. So we’d pack up, load the Cutlass, and make one last trip down the block to say goodbye. That’s when something wonderful would happen. With a little smirk and a rustle of thin paper, Grandma would hand us each a brown bag and say, “Pick out some candy.” The first time she did this, I was too excited by the idea of free sugar to question anything. But after a few repeat performances, it started to sink in: we weren’t paying for this stuff. My parents later claimed she was shutting off the security cameras during the heist, but that might’ve been for dramatic effect. I also never saw her pay for the candy herself, but honestly, I wasn’t exactly auditing her register. What I do remember is her smile—wide and mischievous—and how much joy she got from watching us lose our minds over Sixlets and candy cigarettes.

And it wasn’t just candy. Back then, cigarette and beer companies advertised directly to children, which meant Grandma had an endless supply of branded swag that needed to be sold or thrown away. Instead, she gave it to us. Hats, posters, foam koozies, and even mesh tank tops featuring the friendly cartoon face of Joe Camel. Which I wore. To school one time, if I’m not mistaken. The ’80s were wild.

All that to say, Grandma was always generous with everything—whether it technically belonged to her or not.

Those little shopping sprees kept on until we relocated to Japan in 1992. By the time we got back, Grandma had retired from Maverick and moved back to Pearsall. There, she continued her service to her family, mostly through food. On any given visit, you could expect a banquet of traditional Mexican food that made my parents’ mouths water. My brothers and I didn’t really have a taste for caldo or menudo, opting instead for meals from the Sonic on the other side of the train tracks.

There were some exceptions: carne guisada, Mexican rice, chorizo and egg breakfast tacos, etc., but my all-time favorite was her tamales. No one makes tamales the way Grandma did. By the time we arrived for our Christmas visit, most of the prep was already done, but there were a handful of times I was able to see Grandma hard at work spreading masa or filling pots. I didn’t (and still don’t) know a lot about how tamales are made; all I know is that they were always hot and ready to eat.

One year, we arrived to find her home in Pearsall saturated with the smell of tamales. I may have smelled them from the curb—that’s how much I anticipated tearing through a dozen now and maybe a dozen later. And though the stove was covered in pots, each containing dozens of steaming tamales, Grandma told us we couldn’t eat them.

Never before or since had the word why been spoken so meekly.

“Sorry, mijo. The head is bad.”

“The what?” I asked.

“The head. From the pig.”

And that’s when I learned where Grandma sourced the meat for her tamales. Did it make them any less delicious? No. But did it change my eagerness to eat them? Also no. I blocked out the image of my sweet little Grandma hacking at a pig’s face and buried it deep down with the time I peed my pants at Sunday School. She would eventually stop making tamales as she got older. They’re a ton of work to make (so I’ve heard), and I think she started forgetting her recipes.

I still like to eat tamales at Christmas, but every year is a desperate, fruitless search for something that even comes close to what Grandma made.

Cruz Verastiqui passed away on June 15, 2025, at the age of 92. Though the door to her tamales and pan de polvo had been long closed, now it is locked forever. It’s easy to focus on food as one of the things I will miss, but it’s more of the overall environment… what it felt like to be around my Grandma. Her home was your home. And while you were there, she took care of you. No matter how old she got. No matter how tired she was.

Her obituary, like many others, mentions service. This is not just a platitude for my Grandma. She served us our entire lives, and her love was unconditional.

Whether it was her food, home, time, or things that didn’t necessarily belong to her, she was always ready to give everything away.

Even her car.

I was only half-listening to Grandma talk to my dad, but my ears definitely perked up on the mention of the broken gas gauge. My little brain was laying the foundations for a lifetime of anxiety, so hearing we would be taking a trip in a car that could run out of gas at any time started up my little maquina de preocupación—my worry engine. My dad was equally confused.

“But Mom, how do I know if we’re low on gas?”

And my grandmother, this woman for whom nothing was ever a problem, said simply, as if my dad were ten years old again, “Pues, the little man will tell you.”

You are out of gas. Now.

I didn’t see her very often in her later years. A couple of birthdays. A few holidays. She eventually fell back to speaking only Spanish, which even after all this time, I’ve never learned. I still tried, though, because if nothing else, my horrible Spanish made her laugh.

It was the least I could do.

A small gesture for a woman whose love and kindness I could never possibly repay.

You can learn more about my grandma’s life through her obituary, available here.